-

Welcome to the Bank of England Museum and to one of our series of short talks about items in our collections. My name is Alison Cook and I am the Museum’s Operations Manager. Rather than telling you about a specific object, the subject of this talk is Operation Bernhard, the attempt by the Nazis to destroy the UK’s economy by flooding the country with counterfeit banknotes.

The initial plan, in 1939, was a simple one. Counterfeiters, who were known to the SS, would be used to forge £30 bn worth of banknotes. The intention was to drop the counterfeit notes from airplanes, all over Britain, causing a loss of confidence in the currency and the economy to collapse.

This initial attempt was codenamed Operation Andreas. In 1941 Alfred Naujocks, an assassin and dirty-tricks operator for Heinrich Himmler, was appointed to conduct a trial run. At that time, British banknotes had a simple, elegant design. The black printing appeared on only one side of the white, cotton-rag paper, with a small image of Britannia in the top left hand corner. In fact, the design of banknotes had changed little since 1855.

A small number of counterfeit notes were sent to Swiss banks to see if they would be spotted. Some of these notes made their way to the Bank of England and were confirmed as being genuine. Despite this successful trial, the political climate in Germany changed. Naujocks, and the plan to drop money from the sky, fell out of favour.

The plan resurfaced in 1942 under the leadership of Friederich Bernhard Krueger, a major in the SS. This time the intention was to finance Nazi intelligence operations by using counterfeit notes to pay spies, and for buying gold and other supplies.

Krueger’s first step in Operation Bernhard was to find prisoners in concentration camps with knowledge of engraving, printing, graphics and banking. He assembled a team of 142 Jewish prisoners at Sachsenhausen camp near Berlin.

The team of prisoners studied vast quantities of genuine white banknotes. They focused on discovering the secret security marks; engraving the image of Britannia, also known as a vignette; perfecting the banknote paper; forging signatures; and, mastering the printing process. At each stage, and at risk to themselves, they tried to delay the project.

The prisoners identified 150 different security marks. These were intentional, minor defects, different for each denomination of note. The flaws had been incorporated into the design of the notes by the Bank of England, as anti-counterfeiting devices. Detection of these intended defects allowed the creation of high quality printing plates for the £5, £10, £20 & £50 banknotes.

But having printing plates was not sufficient. They needed something on which to print the notes. Bank of England banknote paper has a watermark and a very distinct feel. Since 1724 it has been made for us, exclusively, by Portals, the specialist paper maker. The Nazis went to Hahnemühle paper mill where they conducted experiments and managed to create paper that had the same “look and feel”. Once printed, the counterfeit notes had to be aged. A team of fifty prisoners, with dirty hands, repeatedly rubbed and folded the notes. This transferred dirt and sweat to the notes, creating the desired “wear and tear”.

The Nazis tried, but failed, to crack the numbering system used by the Bank of England. Instead they were forced to re-use serial numbers from genuine banknotes.

The first counterfeit note was detected in 1943. This had passed through a British bank in Tangiers, in Morocco. At that time, the serial numbers of notes that had been withdrawn from circulation were recorded in large, leather-bound ledgers. An eagle-eyed Bank clerk noticed that the note in front of him had already been “paid”, so had to be a forgery. Senior officials at the Bank of England were, reluctantly, very impressed with the quality of the counterfeit.

When it became clear to the Nazis that defeat was inevitable, the prisoners were moved from Sachsenhausen in Germany, to a camp in Austria. The intention was that they would continue to produce counterfeit banknotes. But fate intervened. Allied forces closed in and the lack of vehicles to move the prisoners, meant that they were liberated by US forces on 06 May 1945.

It is thought that most of the counterfeit notes produced were thrown into Lake Toplitz, near Ebensee in Austria. The Nazis had hoped that the depth of the lake would prevent the recovery by Allied forces of the banknotes and printing plates. But that is not the end of the story.

In July 1959, reports began to appear in newspapers that a diver had found wooden boxes, containing counterfeit £5 banknotes, in Lake Toplitz. A few weeks later, press reports suggested that printing plates had been recovered. The quantities and “value” of banknotes involved were significant: amounts of £700 mn were mentioned in the press. But, by November, the newspapers were reporting that the counterfeit notes only had a face value of £9 mn and had been destroyed at the Austrian National Bank.

In 1943, the Bank responded to Operation Bernhard by withdrawing from circulation all notes with a face value higher than £5. Although it is thought that most of the counterfeits were thrown into Lake Toplitz, a small number turned up in circulation for a number of years after the war. It wasn’t until some 20 years later, in 1964, that a £10 note was reintroduced. This was followed by the twenty in 1970, and by the fifty in 1981. All of these notes had much more sophisticated, colourful designs than the elegant white banknotes they replaced, making them harder to counterfeit.

One of the prisoners liberated by US forces was Adolf Burger, a Jewish Slovak printer-turnedunwilling counterfeiter. If you want to learn more about Operation Bernhard, his book, “The Devil’s Workshop: A Memoir of the Nazi Counterfeiting Operation”, published in 1983, provides a firsthand account.

I hope you have enjoyed hearing about Operation Bernhard and please, do look out for other talks in this series.

Gold

-

Welcome to the Bank of England Museum and to one of our series of short talks about items in our collections. My name is Miranda Garrett and I am the Museum’s Collections and Exhibitions Manager. The subject of this talk are the gold bars in our Museum and gold more generally.

We have two full-size gold bars on display at the Bank of England Museum. One of these is in a very secure touch case in the Rotunda, the round room at the back of the Museum. This is by far the most popular item we have on display. Visitors can put their hand through a small hole in the Perspex case, palm facing upwards, and try to lift up the bar, which sits inside a steel cage, on rubber rings. Lifting the bar is a challenge for many of our visitors, as it weighs about 12.5 kilograms, that’s nearly 28 pounds! We will tell you more about the size of an average gold bar later.

The price of gold is set internationally twice a day. Each day we post the current value of the bar next to the display case. The price of gold can fluctuate significantly depending on economic conditions and this affects the value of the bar. At the start of 2020 the bar was worth just under £460K but by August, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, its value had increased to more than £625K.

The bars in the Museum are London Good Delivery bars, also known as LGD bars. This means that they have to meet certain standards in terms of their size, shape and weight.

For historical reasons, the weight of gold is given in troy ounces, named after the medieval town of Troyes, in France. And, somewhat confusingly, at 31g, a troy ounce weighs slightly more than an Imperial ounce. LGD bars must weigh between 350 and 430 troy ounces.

LGD bars also have to be at least 99.5% pure. Gold purity has a unique measure known as fineness, measured in parts per thousand. Bars have to be between 995 and 999.5 fine to meet LGD standards. The gold bar in our touch case has a fineness of 997.9.

Bullion traders measure purity in fineness but jewellers talk about carats. In terms of comparing the two, you need to keep in mind that 24-carat gold is fine ie 99.9% pure. But 18-carat gold is 75% pure and 9-carat gold is only 37.5% pure.

Gold is mined, refined, and then smelted into bars or coins. The value of a bar depends on its weight in troy ounces, its purity and that day’s gold price. No gold bar can ever be 100% pure. Common impurities include iron, zinc, silver, copper and bismuth and these can slightly affect the colour of the bar.

Gold bars are roughly the size of a house brick but with sides that slope inwards. This unique shape is known as a trapezohedron. At least one of the sides, usually the broader base, will have indented writing on it. This includes the refiner’s name or mark, the country of origin, the fineness of the bar, the year of manufacture and a serial number for identification purposes. The surface can be silky smooth, or slightly rough and depends on the inner surface of the mould in which the bar was cast.

Gold is unique because it has some very useful chemical and physical properties. These make it a very important and valuable resource for the jewellery, dentistry, medicine, aviation and electronics industries.

Of all the precious metals, gold is the most popular as a form of investment. Investors generally buy gold as a protection against economic, political or social upheaval. In times of economic uncertainty, the stock markets tend to fall and the price of gold rises. When confidence returns to the stock market, the price of gold tends to fall again.Despite this volatility, many central banks hold gold as part of their reserves. The Bank of England is thought to be the second largest gold custodian, after the US Federal Reserve Banks. We stack the gold in the Bank’s nine vaults on wooden pallets. We can store up to 80 bars on a pallet, which then weighs approximately 1-tonne. We normally stack the pallets 4-high, and in some places, we can stack them 6-high. But, we have to ensure that we do not overload the floor as the Bank was built on soft clay soil.

As the central bank of the United Kingdom we hold about 24,000 bars, or 320 tonnes, of gold on behalf of H M Treasury. Nevertheless, this is only a small proportion, approximately 6%, of the 400,000 bars in our vaults. Most of the gold we look after is for other central banks.

To conclude this talk I want to ask and answer a frequently asked question. “Has any of the gold ever been stolen?” The simple answer to this is “no”.

However, it’s said that, back in 1836, the Directors of the Bank received an anonymous letter advising that the writer had been in the gold vault. Melodramatically the letter writer offered to meet the Directors in the vault at any hour of their choice.

Although initially sceptical, the Directors were finally persuaded to meet one night in the vault. At the appointed hour a noise was heard from below the floor and a man suddenly appeared by pushing aside some floorboards. This sewer man had been repairing the sewers and had discovered an old drain, which ran directly under the bullion vault. The contents of the vault were quickly checked and nothing was found to be missing. The Bank rewarded him with a gift of £800 for his honesty.

Today that £800 is worth approximately £92,000. Or, to put it into a golden context, less than a quarter of the value of a LGD gold bar.

I hope that you have enjoyed hearing about the Museum’s gold bar and gold more generally. Look out for other talks in this series.

Thank you and goodbye.

Britannia

-

Welcome to the Bank of England Museum and to one of our series of short talks about items in our collections. My name is Miranda Garrett and I am the Museum’s Collection and Exhibitions Manager. The subject of this talk is Britannia and her long association with the Bank of England.

There are many images of Britannia in our Museum. She appears on banknotes, banners, wax seals, a flag and a sail.

The largest Britannia in our Museum is a relief sculpture on a wall. Relief is a sculptural technique where the sculpted elements remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term relief is from the Latin verb relevo, to raise. The relief is approximately 1m in diameter and visitors can run their hands around the circumference. Sitting inside a circular border, Britannia is facing to the right, and looks like a physically strong woman, dressed in flowing robes. She holds a spear in one hand and an olive branch in the other. She has shoulder length hair worn untied. She is perched on her shield, protecting a huge pile of coins at her feet. You might be interested to know that we ask younger visitors to count these coins as they complete one of our activity sheets. There are 55 in total.

But let’s get back to Britannia. Who was she?

Britannia is Latin for Britain. After the Romans conquered Britain in 43AD, their new province of Britannia covered the island as far as Scotland, which they called Caledonia. It was also the name they gave to the female personification of the island. Britannia first appeared on Roman coins in 119AD, as a Roman goddess, armed with a trident, (a three-pronged spear) holding a shield and wearing a helmet. She looked quite similar to Minerva, the goddess of wisdom and war. The helmet and spear or trident you see portrayed with Britannia are all symbols associated with war.

So why is Britannia sometimes shown carrying an olive branch, which is usually a symbol of peace? After the fall of the Roman Empire, Britannia disappeared from our coinage. She resurfaced during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, appearing in contemporary drama and literature, where she symbolised England’s growing maritime empire. She reappeared on coins in the reign of Charles II. This time, Britannia had a more peaceful aspect, represented by the olive sprig in her right hand. In modern coinage, Britannia appeared on the 50p piece issued from 1969 to 2008. On this coin, she is sitting next to a lion with a shield resting on her right side, holding a trident in her right hand and an olive branch in her left.

And, what about Britannia’s association with the Bank? How did this come about?

Britannia is a very important part of the Bank’s history, from way back when the Bank was founded in 1694 all the way through to its role today producing banknotes for England and Wales.

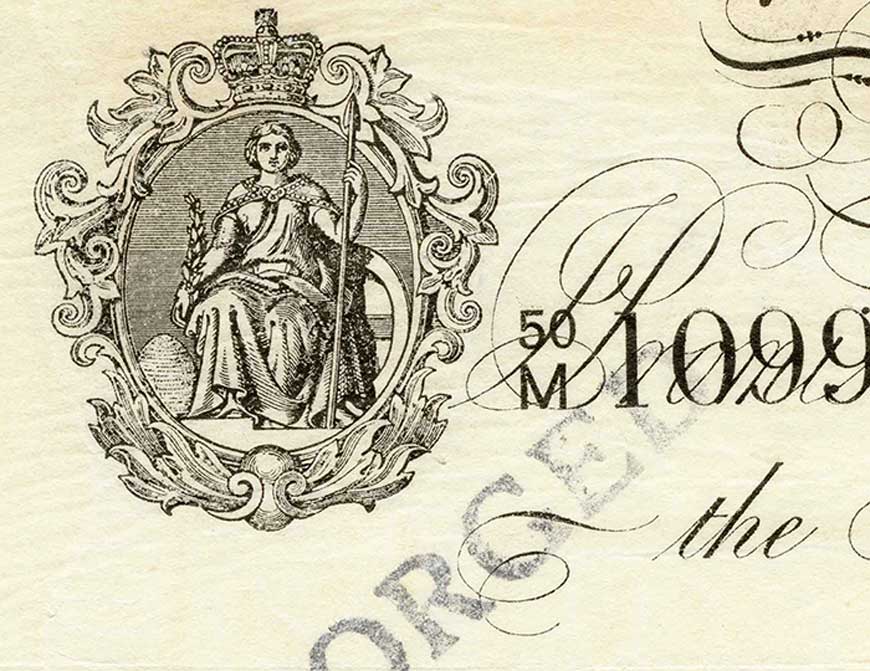

During their first meeting in 1694, the Bank’s Court of Directors chose a new seal and symbol for the Bank of England. They picked Britannia, sitting and looking over a bank of money. In one form or another, Britannia has appeared on every printed Bank of England notes since then. We don’t know

why the Directors chose Britannia, but they might have been influenced by the Royal Mint, who had recently used Britannia on new copper coins.Britannia has appeared on every Bank of England note since, but her design has changed over the centuries to reflect changing fashion. One of the most famous banknote Britannias was designed by Daniel Maclise. This design appeared on banknotes from 1855 to 1956. This is a very clear and simple image of Britannia. Unlike most representations, it shows her facing forward rather than sideways. As might be expected, she is holding a spear, olive branch and a shield. She sits inside a very ornate, scrolled, oval border, similar to that found on a Victorian mirror.

Over the years, as the design of our banknotes has become more complex, the image of Britannia has become smaller. The notable exception to this is the new £20 polymer note, issued in February 2020. The image of Britannia on the front of this new note is both larger and more prominent than on earlier notes in the series. On the polymer £5 and £10 notes, Britannia was printed in one colour, with shades of blue on the £5 note and shades of orange on the £10 note. On the new £20, she appears in purple, the main colour of the £20 note, against a dull gold background.

There are many examples of our banknotes on display in our Museum, spanning more than 300 years of the Bank’s history. Our displays include a couple of printing plates for the £50 note that was in circulation from 1994 to 2014. You can touch the plates and feel the indentations of the banknote design, including the large oval-shaped representation of Britannia.

And finally, even today, Britannia doesn’t only appear on the banknotes we issue. She is still there in the Bank of England’s logo, which appears on all of our publications and reports.

I hope that you have enjoyed hearing about Britannia and that you will want to listen to other talks in this series.

Thank you and good bye.

1694 Royal Charter

-

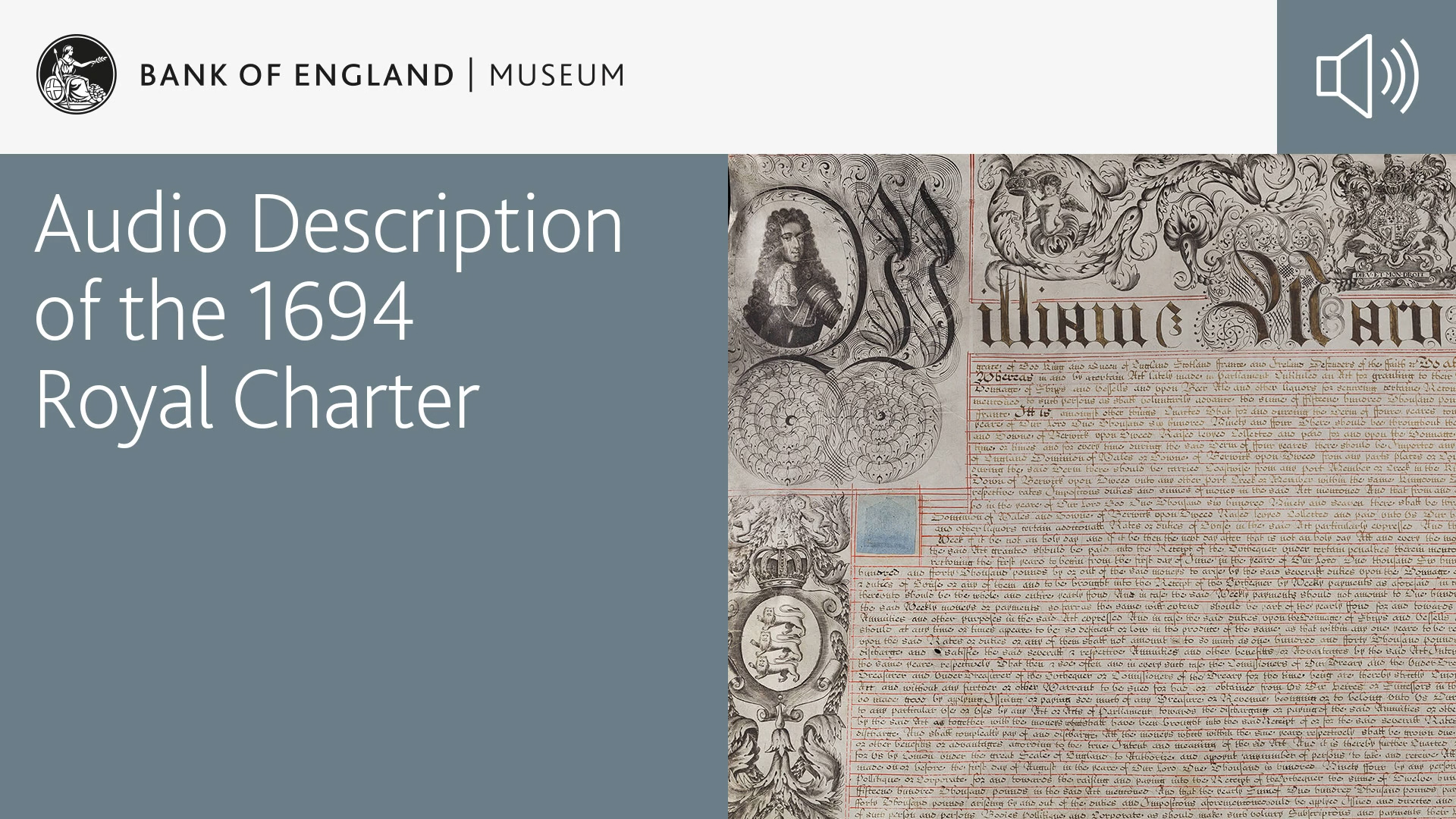

Welcome to the Bank of England Museum and to one of our series of short talks about historical items in the Museum. My name is Miranda Garrett and I am the Museum’s Collection and Exhibitions Manager. The subject of this talk is our 1694 Royal Charter.

The original Charter is hand written on treated animal skin, known as vellum, and is held in the Bank’s Archive. A copy of this Charter is on display in the Museum.

The Museum’s copy is in a floor-to-ceiling display case which runs the full length of one wall of a small, dimly lit gallery. The Charter has pride of place in the middle of the display case and measures approximately 100 cm wide. About 80 cm of its length is on display, including the top and the bottom of the document. The rest is folded out of the way in gentle pleats.

The Charter is incredibly ornate. The text is framed with black ink decorations. At the top and centre of the document is the Royal Crest. This coat of arms is the badge of the monarchy. It appears on the Charter because the document bears the names of King William III and Queen Mary II.

The Royal Crest shows a lion and a unicorn, both rampant i.e. standing on their back legs. Between them, held in their front paws and hooves, is a four-part shield. The top left quarter contains 3 sidefacing, standing, or statant lions. These are stacked vertically. Moving clockwise, the top right quarter contains a single rampant lion. The bottom right quarter contains three statant lions. The bottom left quarter contains a harp. At the top of the shield sits another, much smaller, lion. This one is in side profile, wearing a crown, with his tail doubling-back over his back. The French words “Dieu et mon droit” which means “God and my right”, appear at the bottom of the crest, between the back legs of the lion and the unicorn.

This royal motto is thought to have first been used by Richard I, who was of French ancestry. Richard is believed to have used this as his battle cry. His choice of words refers to the concept of the divine right of the monarch to rule. Elements of the Royal Crest, including both rampant and statant lions, crowns and harps, are repeated in the ornate decorations that run down both sides of the document.

In the top left hand corner of the Charter is an image of William III, who was on the throne when the Bank was founded. He is wearing a wig of long, black, curly hair. The wig sits well back on his head, suggesting a receding hair line, and extends half-way down his upper arm. Also visible on William’s left shoulder and upper chest is part of a suit of armour, comprising overlapping plates. William’s portrait sits in a decorated oval frame, which forms part of a distorted and exaggerated capital “W”. Above, to the right and below this oval are intricate, repetitive patterns of circles-within-circles and curved lines.

The letter “W” is the first letter of “William”. This is followed by the words “and Mary By the grace”, with a highly decorated capital “M” and capital “B”. Although only the first two letters of the word “grace” appear in the title row, the sentence is completed on the next line as “grace of God, King and Queen of England, Scotland, France and Ireland, Defenders of the Faith”. This is followed by the words of the Bank of England Act 1694 which established the institution. The Charter also mentions the Commission that collected money from the initial subscribers and the right of these subscribers to be paid interest on their investment. The rest of the Charter sets out the conditions under which the Bank would operate.

Although the words at the end of the Charter date the document to 27 July 1694, it wasn’t actually signed and sealed until 10 July 1695. Unfortunately Mary died of small pox in December 1694. So, although her name appears with William’s at the top of the document, only William physically signed the Charter.

Attached to the bottom of the Charter is a wax seal. Historically, wax seals were an integral part of the process of signing official documents. They typically bore the owner’s identifying emblem or coat of arms. After melting, sealing wax hardens to quickly bond to parchment, ribbon, wire or string. This serves as a security feature as any attempts to interfere with the seal, results in visible evidence of tampering.

The seal on the Royal Charter measures about 15 cm in diameter, is about 1.5 cm thick and is a dark, dirty brown colour. It has a raised, woven rope effect rim, with letters which are no longer legible, running around inside this. On the front of the seal is the raised impression, in side profile, of a rearing horse. The rider sits in a twisted and very unnatural position. All of the front of the top half of his body is turned toward the viewer but his head is in side profile, looking forward. His cape streams behind him and he is carrying an almond shaped shield, slung low across his right leg. The seal is attached to the Charter by plaited, straw-like string. This is sewn into the bottom of the Charter in a simple diamond shape, runs all the way through the seal and extends beyond the bottom of it by a good 5 cm.

Finally, you might be aware that the mission of the Bank today is that of “promoting the good of the people of the United Kingdom by maintaining monetary and financial stability”. This is very similar to the Bank’s mission when it was founded. In fact the Royal Charter includes the words “to promote the publick good and benefit of Our people”. So, although the Bank today is very different from the one founded in 1694, our primary role has not changed.

I hope that you have enjoyed hearing about the Bank’s 1694 Royal Charter. Look out for other talks in this series.

Thank you and goodbye.

“The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street” (a cartoon)

-

Welcome to the Bank of England Museum and to one of our series of short talks about items in our collections. My name is Miranda Garrett and I am the Museum’s Collections and Exhibitions Manager. The subject of this talk is a famous cartoon by James Gillray.

James Gillray was born in Chelsea in 1756. He apprenticed as an engraver, specialising in security documents, such as banknotes. But he quickly tired of this. After a period wandering around the country with a company of strolling players, Gillray returned to London and began to study engraving at the Royal Academy. He is known to have supported himself by engraving and is also thought to have issued numerous cartoons during this period, under a variety of names. He went on to become a remarkable cartoonist and was particularly famous for his political and socially satirical works.

Gillray produced more than 1,000 cartoons during his lifetime. We have copies of many of these in our collections but one is particularly important to us. Why? Because it is the first time that the Bank of England’s nickname of “The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street” appeared in print.

The background to the cartoon is as follows. France declared war on Britain in 1794. Three years later, in February 1797, several hundred French troops landed at Fishguard on the Welsh coast. This was perceived as a long-expected French invasion, and although the invaders were quickly rounded up, sparked wide spread panic. At that time people could exchange banknotes for gold, on demand, at the Bank of England. Consequently, we were inundated with exchange requests and, in less than a fortnight, our gold reserves shrank in value from £16mn to less than £2mn. This was not sustainable, and the Government released us from the obligation to pay notes in gold. This was known as the ‘The Restriction Period’, and continued until 1821, some six years after the war with France had ended.

Unsurprisingly, some politicians were horrified by the Government’s actions. The MP, and notable playwright, Richard Sheridan, described the Bank as, ‘an elderly lady in the City who had..… unfortunately fallen into bad company’. Gillray latched onto these words and, on 22 May 1797, published a cartoon called “Political Ravishment or the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street in Danger”.

The cartoon is set in the Bank of England’s “Rotunda”. At that time, this was a circular public office in our Threadneedle Street building. In the distant background you can just make out the clerks sitting at their desks. In the front right foreground, lying on the ground, is piece of paper titled “Loans”. This is a nod to the continual demands of the government of William Pitt the Younger to borrow money from the Bank.

Taking up most of the foreground of the cartoon are two figures, a man and a woman. The man is William Pitt. Skeletal, freckle-faced and pointy-nosed, he pretends to woo an elderly woman, who represents the Bank. But Pitt was actually after our gold reserves, shown as gold coins in the woman’s pocket, and the gold-coloured, padlocked money-chest on which she sits. Pitt was known to be tall, more than six foot, and is shown leaning forward in a way that comically exaggerates the length of both his spine and legs. The red trim, collar and cuffs, of his royal blue frock coat, match the tiny shoes of the woman. Pitts’ right arm and hand encircle the woman’s waist and his left is pushing its way into her pocket of coins.

The elderly woman has exaggerated and unflattering features including a long, hooked nose and matching chin. Her arms are raised above her head with the wide sleeves of her dress flapping frantically, her claw-like hands outstretched in horror. Her gown is pale in colour and made of the new, and very unpopular, £1 and £2 notes. These had been issued to replace gold coins in circulation. The woman’s dress is complemented by a banknote headdress in her grey hair and a pair of ribbons, also made from banknotes, which hang from the back of her head.

Above the woman’s head is a speech bubble. She is clearly concerned for her virtue and is trying to attract attention and assistance. She shouts “Murder! O you Villain! Ravishment! Ruin!”

Although he died more than 200 years ago, Gillray is still widely regarded as one of Britain’s greatest cartoonists. His work continues to inspire that of his modern counterparts.

I hope that you have enjoyed hearing about James Gillray and our nickname. Look out for other talks in this series.

Thank you and goodbye.